Origin and Overview

Imagine you're journeying through history and how societies change over time, like exploring a vast, intricate maze. In this maze, we come across a special way of understanding these changes, introduced by a philosopher named Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. He came up with the Hegelian debate, like watching a movie where two characters, Idea A and Idea B, are at odds. Idea A wants things one way, and Idea B wants them completely differently. Their clash creates a lot of tension and drama, but by the movie's end, they combine the best parts of both ideas into Idea C, which is way better and liked by everyone.

Hegel thought this movie-like process wasn't just for entertainment but happened all around us in real life, constantly shaping history and how societies evolve. He saw every big change as starting with a situation (our Idea A) that meets resistance (our Idea B). The friction and fight between these two lead to a brand new situation (our Idea C) that improves on both ideas.

This method, part of Hegel's bigger picture of "absolute idealism," offers a detailed way to look at how history moves forward and societies transform. It's like a key to understanding the past, politics, and personal arguments, and it is also about how we can work together to find better solutions. Hegel's approach teaches us that through conflict, we can blend the best ideas from opposing sides to create something everyone prefers. His influence stretches far and wide, making us see that this process of conflict and resolution is a fundamental part of human progress.

Embedded in Hegel's expansive philosophical doctrine of "absolute idealism," this method asserts a unique perspective on historical progress. Hegel meticulously argues that the forward march of history is inherently driven by the dialectical interplay between conflicting forces, which he distinctly categorizes as "thesis" and "antithesis." This clash, marked by inherent tensions and contradictions, inevitably leads to a harmonious resolution known as "synthesis." This synthesis ingeniously integrates the most compelling elements of the thesis and antithesis, thereby catapulting society onto a novel developmental plateau.

This dialectical framework did not merely contribute a new lens through which to view the progress of history; it actively reshaped intellectual discourse, especially within Hegel's homeland of Germany during the pivotal periods of the 19th and early 20th centuries. The profound influence of Hegel's dialectic transcended its original philosophical bounds, igniting scholarly debates and inspiring an array of thinkers across diverse fields.

It offered a transformative approach to dissecting the complexities of philosophical thought, historical evolution, political science, and sociology. Through its dynamic model of conflict and resolution, the Hegelian dialectic has indelibly marked the landscape of intellectual inquiry, providing a robust methodology for analyzing the underlying forces that drive societal change and development.

Prominent People in the Field

In philosophy and social theory, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels emerged as monumental figures who deeply integrated Hegel's dialectical framework into their intellectual endeavors, significantly molding their theoretical landscapes. Marx, in particular, ingeniously repurposed the Hegelian dialectic to underpin his theory of historical materialism. Through this lens, he argued with compelling clarity that the engine of historical development is primarily fueled by the conflicts arising between different social classes. This adaptation spotlighted the dialectic's capacity to dissect and explain the complex dynamics of societal evolution and class struggle.

Beyond the foundational contributions of Marx and Engels, the Hegelian dialectic found resonance and reinterpretation among a diverse assembly of thinkers, showcasing its adaptability and enduring relevance across various fields of thought. Herbert Marcuse, Theodor Adorno, and Max Horkheimer, key figures of the Frankfurt School, harnessed the dialectical method to critique and understand contemporary society's cultural and ideological underpinnings. Their work, deeply infused with Hegelian dialectics, offered incisive analyses of the role of culture, mass media, and technology in shaping human consciousness and social relations.

Moreover, the Hegelian dialectic's impact reached the post-structuralist philosophy domain, with its principles notably influencing the work of the French philosopher Jacques Derrida. Derrida's deconstructive approach, while distinct, engaged with the debate in innovative ways, exploring the interplay of text, meaning, and interpretation. His engagement with Hegelian themes underscored the dialectic's flexibility and potential to foster new modes of philosophical inquiry.

Through their varied engagements with the Hegelian dialectic, these thinkers expanded the scope of dialectical analysis and enriched the intellectual heritage of Hegel's work. They demonstrated the dialectic's unparalleled ability to navigate the complexities of social and historical phenomena, affirming its role as a pivotal tool in the ongoing endeavor to understand and critique the world around us.

Examples of Hegelian Dialectic

Karl Marx's examination of class struggle serves as a prime illustration of the Hegelian dialectic at work, where he foresees the intense clash between the capitalist class, who own the means of production, and the working class, who sell their labor, as inevitably leading to the formation of a socialist society. This society, Marx predicts, will be distinguished by its collective ownership of the means of production. Marx's prediction applies the dialectical method by presenting the capitalist system as the thesis, which provokes the antithesis in the form of working-class resistance. The resolution, or synthesis, emerges as a new societal structure—socialism—which reconciles the conflict by transforming production's economic and social relations.

Similarly, the Civil Rights Movement in the United States vividly showcases the dialectical process through its struggle against racial segregation and discrimination. This period of American history frames racial segregation as the thesis, directly opposed by the civil rights activists' demand for equality and justice—the antithesis. The vigorous confrontation between these opposing forces yields a significant synthesis: enacting civil rights legislation that effectively dismantles institutional segregation and discrimination. This legislative change marks a pivotal moment of synthesis, reflecting a societal shift towards greater racial equality and justice, thus embodying the Hegelian notion of progress through dialectical tension and resolution.

These examples highlight the Hegelian dialectic's profound utility in analyzing and understanding social change. By tracing the conflict between opposing forces to their eventual resolution in a higher state of order, the dialectic offers insights into the mechanisms of societal transformation and progress. Whether examining the evolution of economic systems or the fight for civil rights, the dialectical method provides a powerful tool for dissecting the dynamic interplay of forces that shape human history.

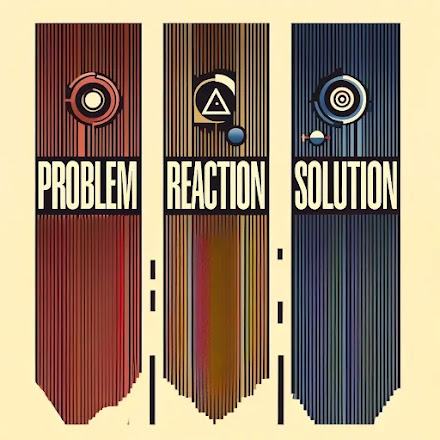

Problem, Reaction, Solution

The "problem, reaction, solution" framework, while often associated with the dynamics of societal change, does not originate from the works of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. Instead, this concept has been attributed to modern interpretations and critiques of political and social strategies. The specific origin of this phrase is somewhat nebulous, but it has been widely discussed in the context of political commentary and analysis. This model posits that an entity intentionally brings a problem to the forefront or exacerbates an existing one, leading to public demand for a resolution. The entity then presents a preconceived solution that aligns with its interests.

Though not a direct extension of Hegel's dialectical method, this framework is sometimes linked to dialectical thinking by illustrating how societal challenges can be navigated to enact changes or introduce new policies. The association with the dialectic likely stems from the process's focus on conflict and resolution, a central theme in dialectical philosophy. However, it's crucial to note that this simplified model needs to encapsulate the depth and complexity of Hegelian dialectics, which involves a more nuanced interplay of contradictory forces leading to synthesis and transformation.

In this framework, a third party initiates or highlights a problem, leading to a public outcry or demand for action. This public response paves the way for the same or a related entity to introduce a solution anticipated or prepared in advance. This sequence emphasizes the strategic creation or utilization of problems to elicit reactions that facilitate the acceptance of new policies, practices, or products that serve specific interests or goals.

By focusing on this sequence, we explore the tactical aspects of societal change, highlighting how challenges can be maneuvered to achieve predetermined outcomes by orchestrating public response and the subsequent implementation of solutions.

Below are three detailed examples that illustrate this concept in various contexts:

1. Environmental Degradation and Green Policies: A corporation or a group of industries may contribute significantly to environmental degradation, a problem becoming increasingly apparent to the public and causing widespread concern. The resulting public outcry demands urgent action to address the ecological crisis.

Capitalizing on this reaction, the same entities may introduce or support "green" policies or technologies that they control or from which they stand to benefit financially. While appearing to solve the initial problem, this solution consolidates their market dominance and potentially sidelines more effective, community-led environmental initiatives.

2. Cybersecurity Breaches and Surveillance Legislation: A significant cybersecurity breach occurs, compromising the personal data of millions of citizens. The breach generates a massive public demand for stronger protections against future cyber-attacks. In response, a government may introduce new surveillance laws to enhance national cybersecurity.

However, these laws also increase the government's surveillance capabilities over the general populace, infringing on individual privacy. Thus, the solution to the cybersecurity problem also expands state power, potentially beyond what is necessary for cybersecurity.

3. Financial Crises and Regulatory Changes: A severe financial crisis exposes the risky investment practices of major banks, leading to public outrage and a clamor for accountability and reform to prevent future crises. In reaction, the government introduces regulatory reforms, purportedly to rein in the financial sector's excesses.

However, critics might argue that the financial industry often shapes these reforms through lobbying and influence. Consequently, the new regulations could entrench the power of large banks even further under the guise of solving the problem of financial instability.

In each of these examples, the "problem, reaction, solution" dynamic plays out in a manner that ostensibly resolves the initial issue but also reinforces or extends the power of those who proposed the solution. While offering insight into the manipulation of crises, this simplistic rendition of the dialectical process risks oversimplifying the nuanced and multifaceted nature of societal change as envisaged in the Hegelian dialectic.

Conclusion

The Hegelian dialectic, with its deep philosophical roots and widespread influence across multiple fields of study, offers a potent framework for analyzing social and historical change. Despite debates over its application, the dialectic's contribution to our understanding of societal evolution remains undeniable. Hegel's dialectic enriches our comprehension of the world by encapsulating the dynamic interplay of conflicting forces leading to transformative synthesis. It underscores the ongoing relevance of dialectical thinking in navigating the complexities of modern society.

0 Comments